A Generational Antidote for Eat, Pray, Love

Diving into the abyss of the self-help shadow

When I first encountered Eat, Pray, Love on a cross-Channel ferry with the man who was, or would soon become, my first husband, I put it gently back on the bookshop shelf and left it where it was. I had a strong sense, even then, that if I read it I would want to leave this relationship and go off travelling all over the place to ‘find myself’.

In fact, it wasn’t until after I had left that marriage - one year in, when his father had terminal cancer and we were about to buy a house to settle down and start a family and I suddenly realised this shit was getting real - that I allowed myself permission to read the book. I’d had so many intuitive whispers not to go through with the marriage. That was never the life I was here for. And, yes, when I read the book, every sentence resonated and I wished I’d read it sooner. Sitting in my new double bed, wrapped in knitted blankets, in a basement flat behind the church I moved into when I left the marriage, tears rolling down my face and knowing - full certainty - that I was here to live a life of spiritual liberation, not the conventional married-with-kids-and-a-middle-class-career I’d been taught to aspire to.

Gilbert’s story, her example, lit the way for many women in my generation to question the conventional life expectations we’d inherited; and it inspired a whole movement of us to find our way differently.

I’m not making LG responsible for my life choices. I’d already been to India in 2006 and spent time at the temple of the Dalai Lama. I’d been practicing and teaching yoga for many years by the time I read the book. My exposure to yogic wellbeing and philosophy had begun with my Grandmother, who taught yoga from the late 70s or early 80s until she retired in the early 2000s. My desire to live a life of spiritual freedom had been born with me, and I could never settle for anything less - even if I had no idea what was even possible beyond the life I knew.

When I left the marriage before I turned 30, my mother asked me: What are you going to do? Well, I won’t die, was my reply. This was both defiance in the face of the unknown, and - looking back now - a gesture towards what was slowly happening to me in the life circumstances I’d created until then. The days I used to imagine letting my car crash into the kerb, just so I could find a free ticket out.

All this, before I’d even read Eat, Pray, Love. But to say that it was influential to the women in my generation is an understatement. Brooke Warner rightly calls the book a ‘cultural phenomenon’.

Since then, we’ve all been on our journeys. Living, loving, eating, praying, meditating… doing the things we’ve done.

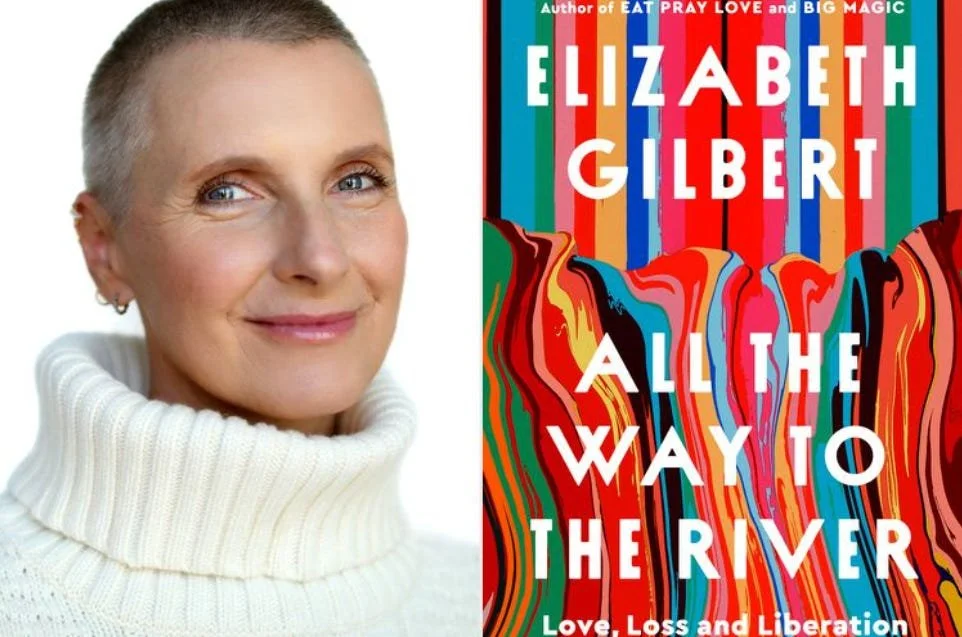

Elizabeth Gilbert - All the Way to the River: Love, Loss and Liberation. Image credit: Debra Lopez, Riverhead Books via People.com

For those who’ve kept walking the path of inner listening, there have been some serious shadows to face in the intervening years. Both personally and collectively. Acknowledging our privileges, our position, the presence of cultural appropriation in those early attempts to remember our way back to a spirituality that seemed as far removed from late-stage capitalism as it was possible to get. And then the messy and damaging co-option of that same spiritual way of life into late-stage capitalism, often by those of us who had started out seeking and idealising it, and always because that’s what the system does - incorporates everything back into itself as a commodity to be packaged and sold.

And what of Liz Gilbert?

Did she sit on her throne, meditating peacefully and smiling graciously at the global white-women’s ashram she’d inadvertently helped to create?

Turns out she didn’t.

She’s been facing the same shit-show of her own shadows, herself.

There’s a lot of divided opinion about Gilbert’s latest memoir, All the Way to the River, about her messy and explosive affair with Syrian-born artist and addict Rayya Elias, and a lot of criticism about the privileged white woman who trampled all over someone else’s cancer story. Those criticisms may be right. But I haven’t read anything in any of the criticism that Gilbert doesn’t acknowledge herself, about herself, within the book.

What began Gilbert’s catapult into the spotlight as what Jia Tolentino calls ‘a particular sort of narrator: always freshly emerging from a dark wood, breathless with revelation’, paved the way for many writers to share their stories - particularly women writers in the spiritual, self-help, and memoir genres that I collectively call Transformational Nonfiction.

These stories of personal liberation intersecting with moments of collective recognition created waves of cultural transformation, igniting an entire industry aesthetic built on the appearance of having just-figured-it-all-out-so-now-I’m-going-to-share-it-with-you-too.

There’s been immense value in this zeitgeist for many women - myself included - and there has also been harm in the veneer of flawless wisdom that’s created a kind of manifestation meritocracy that promises we can have it all while erasing the realities of social and structural inequality.

Yet that heady and breathless narrative voice of early Liz Gilbert strains back against itself in All the Way to the River as she writes with ‘an approach of total humility, the recognition of a fundamental fallibility’ as Tolentino comments in the New York Times article that began much of this debate.

It’s that fundamental fallibility that interests me here.

This is not the polished and complete answer-to-everyone’s-prayers-and-problems kind of spiritual memoir that people were probably expecting from the woman who literally wrote the book on it.

It’s the painful and excruciating slow dawning of realisation that we are all - still - fucked up and fundamentally flawed.

“You found your darkness, Dude” Rayya says to Liz.

Gilbert’s revelations and personal accountability within this recounting of a period of her and Rayya’s lives, which was partially lived out in public and on social media and partially hidden in shameful secrecy, are at times wincingly breathtaking in their brutal honesty.

Wait, did she really just tell us exactly how she planned to murder her crack-ravaged lesbian lover?

What?! She just admitted to tying-off Rayya’s arms and legs to help administer her heroin dose more cleanly…

If I were her writing coach, I think I might have questioned those decisions and suggested greater caution. But Liz has raised the bar on writing authentically.

There she is in the book, bare and stark. And those darkest moments carry us - the readers - into the depths with her. I resonated with her research and reflections on co-dependency, and about how this is a cultural phenomenon many women have been born and socialised into. Yet she never lets that take away from her own personal responsibility and self-accountability.

Despite this, it’s not a book of self-flagellation.

When I work with writers of transformational nonfiction, it’s usually the messy first draft where so much of the working out and alchemical self-discovery is happening in real time. The energy of getting the story down and out. Which transforms the writer into the person they need to become to write the redraft: the version of the book that’s for the readers. It’s through this integration of their own shadow material that they become the medicine keeper for their particular brand of wounded-healer wisdom.

Whatever self-flagellation Liz Gilbert may have had to put herself through in her own writing and recovery process, she doesn’t turn the final pages of this memoir into a place for martyrdom.

All the Way to the River gives us the jubilance of Rayya’s character and the exultation of a love affair that blazed bright before it burned out.

Perpetually discovering and discarding God on the bathroom floor, the book reminds us that we are loved, exactly as we are, despite the endless, reckless, shit-show of our lives.

It’s that, I think, that makes this another powerful memoir for our collective historical moment.

Liz takes us through the intoxicating firestorm of how it feels - at a personal level - to witness the heartbreaking devastation of the one you love, the thing you have depended on, even as that one is sick and addicted and not going down without a fight, and determined to take everyone else out as she dies… Even as you recognise in the other a mirror of yourself.

“Aren’t we all running out of road here?” Liz asks, as Rayya recovers her sobriety enough to ask for forgiveness when her time is so perilously short.

Aren’t we all running out of road?

With the converging global crises escalating daily; rising technocratic fascism putting particularly Black, Brown and gender nonconforming people’s lives at genuine, violent risk; and end-times climate chaos showing up as elemental extremes.

All the Way to the River reminded me of the poignancy of the recent Stephen King film, The Life of Chuck - in which Charles Krantz is dying, age 39, and the multitudes of people whose stories his life has intersected with experience his personal tragedy as the death and destruction of the living universe itself. Stars blinking out and constellations imploding in the night sky as his kidneys fail and organs collapse. Phones no longer connecting calls as his body and mind deteriorate into death. And loved ones clinging to each other for support as they find themselves learning to both surrender and bear witness to the end of the world.

And, by the end of Liz’s story - it doesn’t just end with Rayya’s death. And it doesn’t end with self-help platitudes of full and final redemption for Liz, the happy protagonist, either.

“We have been here before” she says. Reminding us, and herself, that the sense of finality and fulfilment that permeated her spiritual awakening in Eat, Pray, Love must, in time, give way to the ongoing shadow work of presence, compassionate witnessing and self-responsibility.

“The capacity of people to find forgiveness in their hearts for each other’s frailties will never stop astonishing me” she says.

The book invites us to be our own compassionate witness while holding ourselves brutally accountable for our own messy dramas. Knowing that there’s no full and final redemption, no easy and glossy perfection.

In the end, there’s only Love.

→ In my next blog, I’ll be exploring Liz Gilbert’s writing craft in All the Way to the River, to give you a Visionary Writing Guide’s glimpse into how it works and how you can do it, too!

If you are a Visionary Writer and you know you want to (need to) write, but your words are getting stuck before they get onto the page, you can subscribe to the stack for regular updates, or get the book, to find out how to break this cycle and Find Your Visionary Writing Voice.