Raising the Bar for Writing Authentically

Let's dive into the Visionary Writing Craft of Liz Gilbert's new book...

The first few chapters take a moment to land, to settle. Initially, Liz Gilbert’s new memoir All the Way to the River felt essayistic to me. I noticed a little internal groan as I registered: it just sounds like a series of Substack essays tacked together. But a few chapters in the book starts to find the momentum of a narrative drive that carries it - not unbroken - all the way through.

It doesn’t sound like Eat, Pray, Love, and it doesn’t feel like it, either.

The book tells a story that is broken, fragmented, fractured, and interrupted by the insertion of poems, prayers, and pictures.

And, to me, that brokenness is the point.

When I speak about writing authentically, here, I’m not talking about the sensational passages of extreme debauchery - although I can imagine they did take a lot of personal courage to share openly; nor am I speaking about the cringeworthy tender moments in which we hear lovestruck dialogue between Liz and Rayya that might be better kept private. Yet both those aspects of the book likely constitute an enormous professional risk on Liz Gilbert’s part, to be seen so glaringly in her falsities and frailties.

In this article, I’m exploring another aspect of the book - often overlooked or misunderstood - its structure. And specifically, the inclusion, insertion, irruption and intrusion of non-narrative, non-linear, or non-verbal elements that perform a function I think many reviewers are missing.

Interior detail from All the Way to the River, Elizabeth Gilbert, 2025.

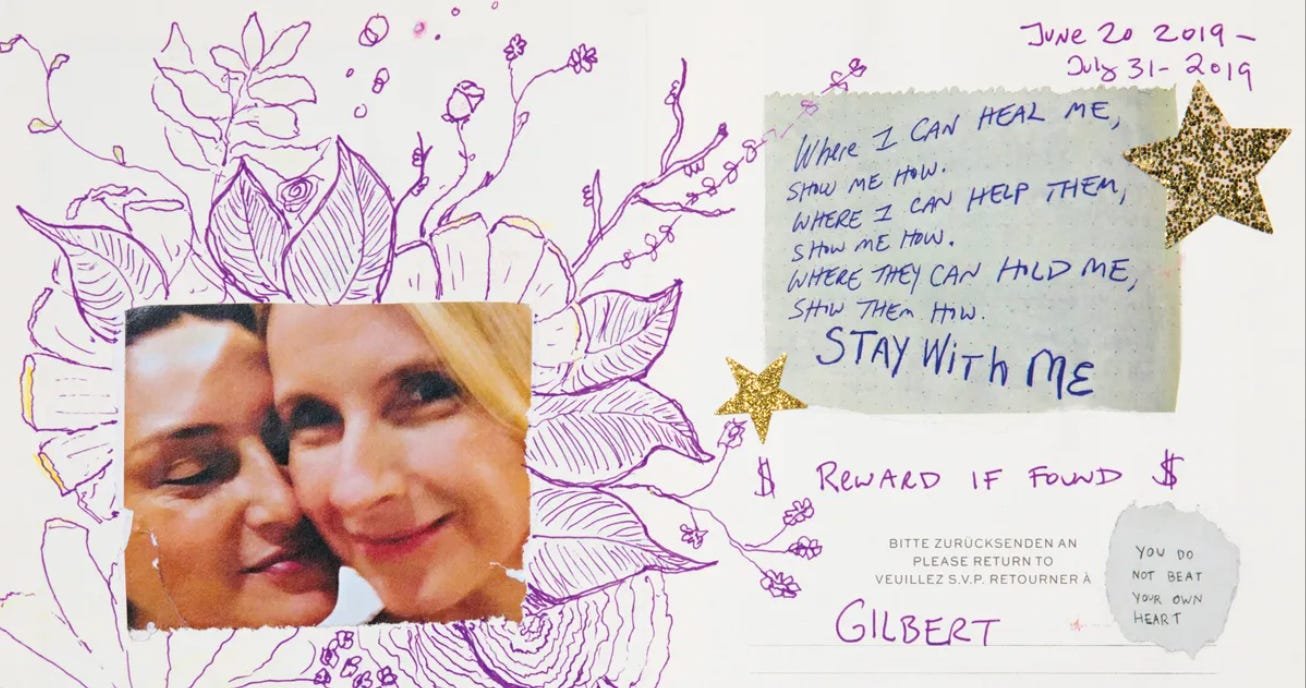

Liz says: ‘This book, with its stories, prayers, poems, journal entries, photos, and drawings, is my very best effort to tell the truth about what happened between me and Rayya Elias.’

That truth is messy, plural, incomplete.

All truth is messy, plural, incomplete.

It’s just that the literary conventions of narrative nonfiction often require the creation of a coherent subject - the narrator (also understood to be the author) - who becomes the organising principle around which the book is built. In memoir, especially, the narrator-author typically tells their story with the benevolent wisdom of hindsight. A position from which they are able - at last - to look back on past events and make sense of the unfolding story of their life.

This is a position which is often unconsciously privileged, and displays cultural markers of assimilation into the dominant hegemony of power and control. The illusion of detached objectivity, the perpetuation of a ‘grand narrative’ of linear progress, the cultivation of a coherent identity. These are the tricks that keep us striving to control, to catch up, to fit in.

But when we step outside the script we’ve been conditioned to rehearse - or when we occupy a position that is already outside the play and banned from the theatre - that illusion may be seen as a lie.

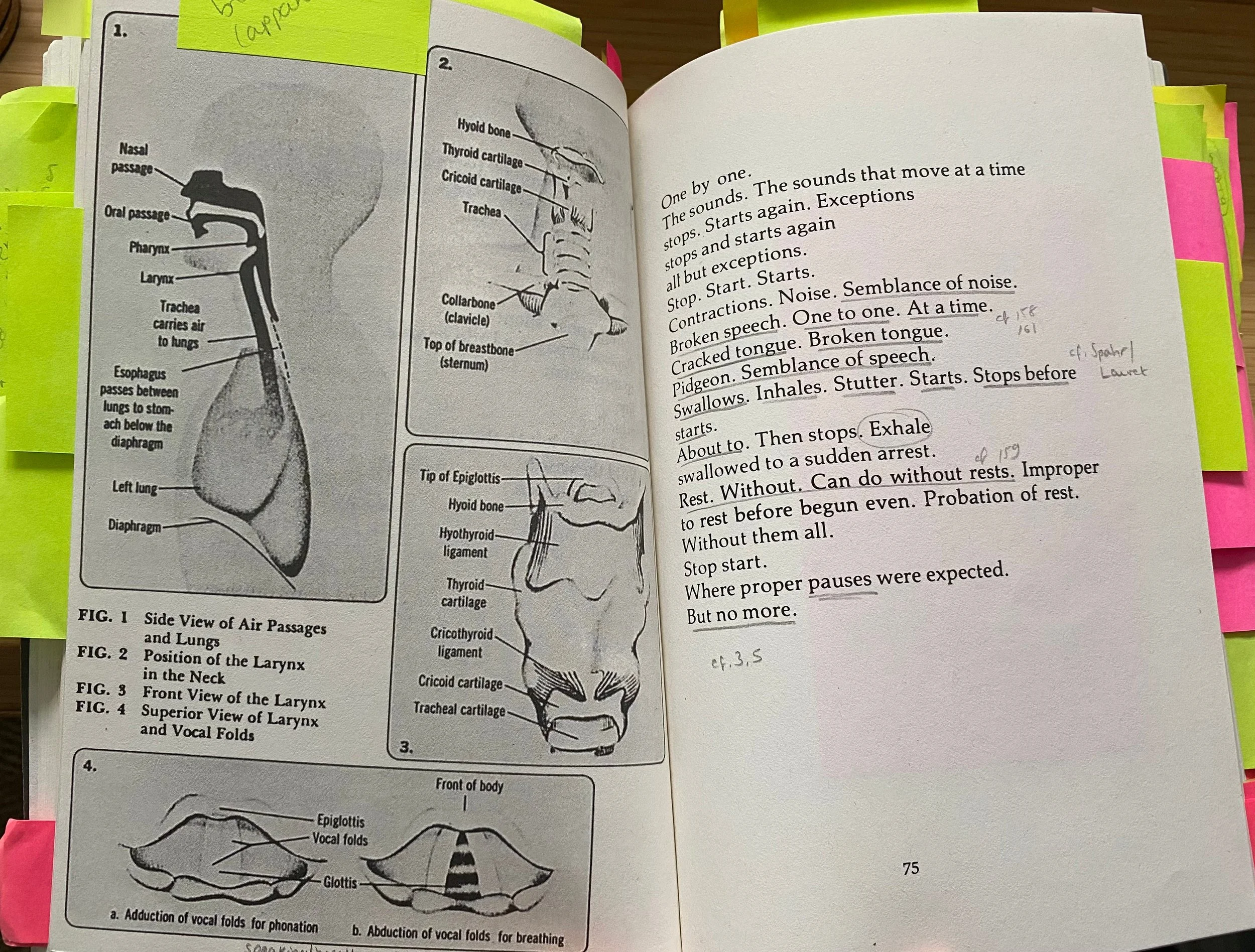

There are many other writers I want to acknowledge before I dive into Gilbert’s book, and I can only acknowledge some of them here. Playing with, politicising, and exploring literary form and structure is not a new concept - although it may feel and seem new to many readers of the traditional memoir genre. There’s a long, deep and rich tradition of cross-genre, multidisciplinary, multimodal, and hybrid works of poetic literature that push the edges of possibility and expectation. Or rather, multiple traditions; more like intersecting threads than a line.

These are books that often invite reader participation, while questioning the nature of what it means to mean, and what it means to belong. Text, images, prose, poetry, diagrams, rituals, music, letters, prayers; all finding ways to coexist in a single work that sings in diverse voices and different tempos. Creating not so much a harmony, but a polyvocal field in which meaning is fluid, conflicting, paradoxical, emergent, fleeting, co-created.

Books such as Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s DICTEE (1980), CA Conrad’s A Beautiful Marsupial Afternoon (2012), Bhanu Kapil’s Ban (2015), Aja Couchois Duncan’s Restless Continent (2016), Patti Smith’s Devotion (2017), Nat Raha’s Of Sirens, Body & Faultlines (2018), Nikita Gill’s The Girl and the Goddess (2020), Alexis Pauline Gumbs’ DUB (2020); and Of Our Spiritual Strivings - a 2021 book by Christina Quarles that weaves with W.E.B. Du Bois’ 1903 hybrid text The Souls of Black Folk.

I encourage you to find some of these books and read them, because they ask questions that may challenge our notions of what it means to write the story of ourselves.

Interior detail from Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s DICTEE (1980).

This is the context I’m drawing from when I read the structure of All the Way to the River by Liz Gilbert.

I listened to the audiobook - narrated by Liz Gilbert herself, with all the emotional nuance of her own voice as she tells the story of her and Rayya’s ongoing love affair. The audiobook version also includes original music and a song by Rayya Elias. In this way, the book opens up to multiple voices, perspectives, experiences, and lives. This is not just the story of one person’s life. Liz explores and explodes the ways she had been trying to make Rayya’s life her own ‘best story’, and instead gives Rayya the last words.

In fact, Rayya speaks repeatedly throughout the memoir; as does God. Liz’s voice is not the only voice we hear; her words are not the only words. She creates space for multiple perspectives that do not always agree, or cohere, with her own.

‘I want to pause for a moment to make a disclaimer,’ Liz says - addressing the reader directly in the broken narrative of her essayistic, episodic style. The telling of this story continually refutes the smooth and shiny veneer that can be common within spiritual memoir or self-help books. Rather than rushing to a sense of resolution that skips over the gritty details, All the Way to the River is committed to staying with the discomfort of the process.

‘Once more, I must be careful here, in the telling of our story. I do not wish to pathologize my relationship with Rayya any more than I wish to idealize it.’ Gilbert is aware of, and keeps drawing our attention to, the tricksy-ness of storytelling: how truth can be obscured for the sake of simplicity; and how language can limit the nuances of complexity.

In the printed book (hardcover, Bloomsbury 2025), the narrative of the memoir is interspersed with - and sometimes interrupted by - prayers, poems, journal entries, drawings, and hand-written affirmations.

Interior detail from All the Way to the River by Liz Gilbert, featured in The Cut

There are places and pages where hand-written words and images erupt onto the page / irrupt into the printed narrative / disrupt / rupture the flow of the story that’s unfolding. While this might not constitute a full on punk-zine aesthetic, it is bold for the genre and gestures towards something that can’t quite be pinned down, defined, or contained. Like Rayya’s life, and their hedonistic love affair, this punk-ish quality rises in waves and rhythms that defy the narrative conventions of serious memoir.

While these extra-textual elements often feel a lot more Rupi Kaur than Patti Smith, at their best, the poems, prayers and drawings may help to break open the oppression of narrative authority, coherence, and conformity. The illusion of a unified ‘self’ who’s figured it all out on our behalf.

I’m not trying to equate All the Way to the River with the other books I’ve mentioned in this essay. Nor am I saying that Liz Gilbert’s ethics and aesthetics are as politically nuanced and considered - she’s unlikely to be operating from the position of being banned from the theatre, even if she’s no longer reading from the original script.

But when I read the book in that context, and she says that this is her ‘very best attempt to tell the truth’, I believe her. I see someone who, regardless of the potential personal and professional risks, is writing to share a story that resists simplification and easy assimilation.

Visionary Writing Craft

Authenticity. Don’t skip the struggles, the challenges, and the restless uncertainty in your writing. Bring your readers on the journey with you. But do consider the ethics and integrity of what your readers can safely hear and receive.

Aesthetics. Consider whether non-textual elements could enhance your readers’ journey, or perform a function that gives additional layers of meaning to your words.

If you’re ready to write your visionary book, you can get my free video training here: How to Write Your Visionary Book Outline.